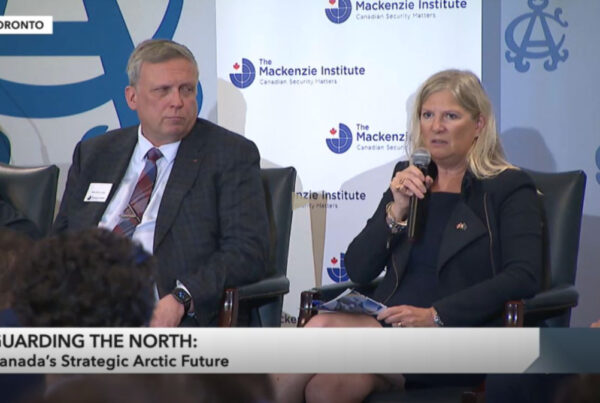

Brian Hay – Chair of The Mackenzie Institute Board of Governors.

Andrew Majoran – General Manager of The Mackenzie Institute.

“The Board of Governors of the Mackenzie Institute would like to thank the Chair and the Committee for the opportunity to make comments on Bill C-51. As you may know, the Mackenzie Institute has worked to make Canadian leaders and the public more aware of the importance of security for more than two decades. Security matters.

Our publications have been cited in numerous newspapers and academic journals in Canada and internationally. Institute representatives have addressed conferences in many parts of Canada as well as in New York, Washington, DC, and in Norway, Great Britain and Israel.

Our Board of Governors is entirely Canadian with members who have lengthy and senior careers in police, military, penal, academic and business sectors. Our Advisory Board, chaired by retired Canadian Major General Lewis Mackenzie, currently has members with senior experience in the security and military sectors in Canada, United States, Great Britain and India.

Before commenting directly on Bill C-51, we would like to make several fundamental observations. First, like many western societies, Canada faces historically unparalleled threats to its physical and social security from economic, ideological, and perhaps perverted religious forces. Strong challenges from any one of these sectors would be sufficient for concern and policy action. Simultaneous challenges, even if uncoordinated, could be extremely taxing, requiring substantial, integrated and well coordinated government action. But as with any government action, care must be taken to ensure that the result of the action actually is as intended and not just another exercise in building bureaucracy.

Second, many point to concern about the impact on the rights of citizens from governments’ actions—this is a valid concern. Rights, much like employee benefits, are much more difficult to take away than they are to give.

Third, to those who express sincere concern about what appears to be government’s invasion of citizen’s privacy, one can remark that perhaps that invasion is now about to become at least more transparent. One should remember ECHELON—an international communications and information sharing program between Canada, United States, the United Kingdom, New Zealand and Australia—has been used by the respective governments to review the communications of the other participant countries and then shared with the government of those citizens. This system allowed “plausible deniability” for governments to claim that they did not “spy” on their citizens.

Private business and personal communications have been increasingly scrutinized by governments over several decades. Fortunately, much of this scrutiny has been to prompt greater transparency in business reporting. However, the growth of the internet and numerous commercially available apps have also allowed for greater access to what was once private information.

The basic issue is perhaps not the intrusion on privacy or the degree thereto. Perhaps the greater issue is—as so well stated by others: why is the intrusion made? By whom? On what authority? How is it done and what recourse does the individual have?

Some may question the need for more and new laws when current laws—well applied—seem to work; indeed, those who would assault our society are being apprehended, such as the Toronto 18 or the more recent train attackers.

Yes, a member of the Canadian Forces was run down and another shot and killed on Parliament Hill by lone wolf attackers. New laws would not have prevented those events happening. Both individuals who committed these heinous crimes were on one or more ‘watch lists’ and had been visited by authorities.

There was, however, little coordination between these authorities.

When Parliament was assaulted, there appears to have been no coordinated pre-plan to deal with such a situation. Why should Canadian security officials consider Canada an exception to attacks when Canada has been identified as a target by overseas terror organizations?

Perhaps the greater problem is not the lack of law or the need for more laws, but the lack integrated planning and coordination of enforcement agencies as they apply the law. Several years ago a municipal jurisdiction in the Ottawa region issued an RFP for a new police radio system. One of the criteria for the bid was that the system should not use, or even carry, the same frequencies as those in adjacent or nearby jurisdictions. Why? The given rationale that was stated to me [Brian Hay] personally was that one jurisdiction did not want the others to eavesdrop on their communications.

Crime and terrorism—like weather—does not respect borders or jurisdictions.

Perhaps it is time to develop a coordination mechanism like the ‘fusion centers’ that are used by our friends to the south. Government needs to enable the effective and responsible sharing of relevant national and local security information across departments and agencies at the operational level. Information is still at the discretion of each department, but there needs to be strict regulations on information sharing to better identify and address threats. No system will be perfect, but a system that has various security organizations working together and sharing information on a daily basis might utilize existing capabilities more than adding more laws.

Thus, the Mackenzie Institute applauds those provisions of Bill C-51 that promote and fund enhanced coordination and information sharing—under appropriate guidelines. We share the concern regarding the possible outcomes of other aspects of the Bill.

For starters, we believe that even more clarity between ‘dissent’ and ‘terror talk’ should also be sought. Bill C-51 will criminalize the advocacy or promotion of terrorism offences Government’s position is that lawful advocacy, protest, dissent and artistic expression is fine (see Part I, Definitions), but how do we define “lawful”? The language must be clear. Reasonable opposition even to the point of demonstration should not be considered “terrorism” unless and until the demonstration becomes destructive. Even then, one needs to distinguish between a riot, which is handled by conventional means, and a terrorist attack, which requires unconventional response.

Changes in existing legislation may be needed, but the implications of those changes must be fully thought through. For example, the CSIS Act is a good piece of legislation but as now written provides CSIS with little direct action authority. With the current security environment, it may be desirable to give CSIS a little more power to act on low-level intervention/threat-diminishment activities (i.e. reaching out and preventing someone from going on the path of radicalization). Today, CSIS is not allowed to tell a parent that their child is about to engage in violent jihad and travel offshore; in the past, the Security Intelligence Review Committee has criticized CSIS for taking these steps to diminish threats, partly because it is not in their mandate.

The act anticipates that, with judicial warrant, “CSIS can break the law and contravene the Charter” according to one commentator. This latter aspect may be an over reach for both the authorizing judge as well as CSIS in terms of the Charter. More balance is needed between desired action and legal reach.

Others have commented on the need for greater independent non-political oversight of how the law is applied. We believe independent, expert, non-partisan oversight of our national security agencies is a better model than political intervention in the process. Australia’s Inspector General is an independent example of how this can be done. Further, the key powers of the new legislation must be clearly subject to judicial review and legal authorization.

Another area of concern is the potential for misuse of the powers granted on a day to day basis under current or new laws. There are examples raised in the media and a few known personally in which existing laws and the powers they convey have been misused either by sloth, poor judgement, or even deliberate misuse. Those charged with the responsibility of upholding the law, are hopefully not automatons. But every human has weak points which is at least good reason why there must be a well-defined and accountable approval process for intrusion on privacy. And even thereafter, there must be an independent, transparent, fair, and expeditious appeal procedure.

Thus, while the Mackenzie Institute applauds those provisions of Bill C-51 that promote and fund enhanced coordination and information sharing—under appropriate guidelines, we share the concerns about possible outcomes of other aspects of the bill. To search personal files at home or in the office requires a valid search warrant; to demand a password for a computer at a border crossing seems quite a reach of the law. Suspicion is no replacement for probable cause. Curiosity is no substitute for evidence. And permitting a judge to break a law or ignore the Charter, to uphold the law or to protect a society based on law, seems at best, contradictory.

Any legislation will be imperfect, regardless of the intent. Improvements are always possible. Moreover the administration of law must be continuously measured for fairness and transparency.

All legal rights may be vested in the Crown. But the actions of the Crown are limited by the toleration of the people, as the Magna Carta demonstrated centuries ago. Thank you.”

Statement Drafted by:

Brian Hay – Chair of The Mackenzie Institute Board of Governors.

Andrew Majoran – General Manager of The Mackenzie Institute.

Kyla Cham – Research Fellow with The Mackenzie Institute