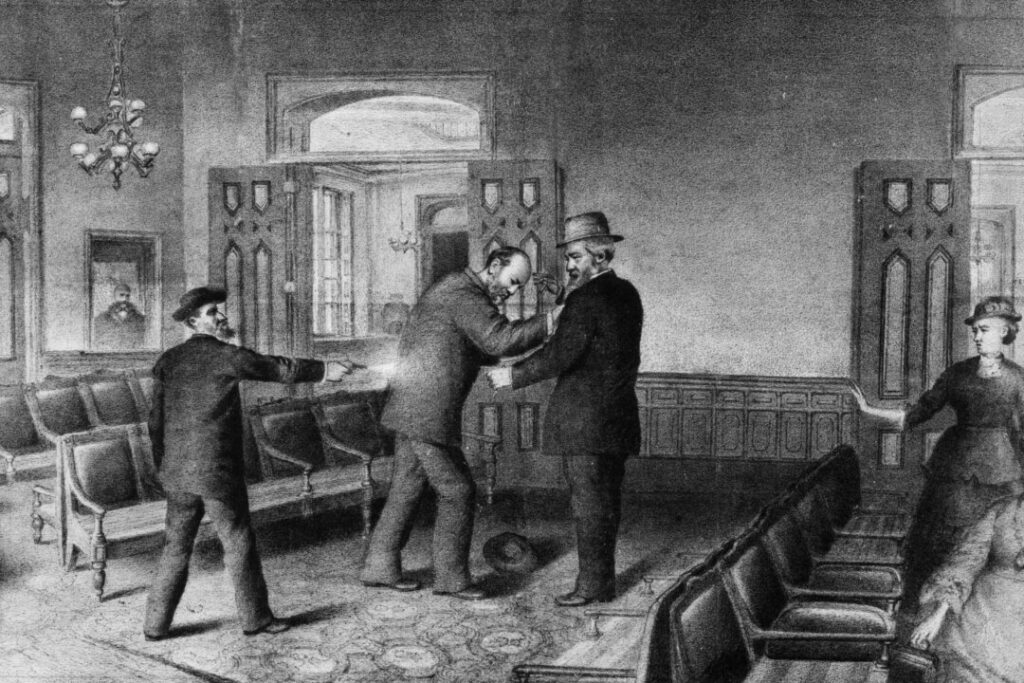

Charles Jules Guiteau, a disillusioned office seeker, shoots U.S. President James Garfield (1831–1881) in the back at the Baltimore and Potomac Railroad Depot, Washington, D.C., on July 2, 1881. Garfield finally died of his injuries on Sept. 19, 1881. (William T. Mathews/MPI/Getty Images)

(Written by Conrad Black. Originally published here in The Epoch Times, republished with permission.)

Commentary

The attempted assassination of former President Donald Trump reminds us of how vulnerable American political leaders are to attacks with guns. In retrospect, all four of the assassinations of American presidents could easily have been avoided.

President Abraham Lincoln was sitting in his box with his wife at Ford’s Theatre in Washington with no security at all, at the end of a terrible Civil War in which 750,000 Americans died in a population of 31 million, and the great animosity of that conflict had scarcely begun to subside. This was a particularly dreadful tragedy for the whole country, not only because Lincoln is generally recognized as the greatest president in American history and possibly the greatest statesman of modern times, but because he was the only person who could accomplish the adoption of a policy of national reconciliation that would have substantially avoided segregation and assured African-Americans the right to vote which, in the southern states, they did not acquire until 100 years later. If President Lincoln had had remotely adequate security, John Wilkes Booth, one of America’s most prominent stage actors, could not have killed him.

President James A. Garfield was shot at the Washington railway station by disappointed office seeker Charles Guiteau just four months into his presidency and died two months later, largely because of incompetent medical treatment. Again, if he’d had one or two competent security personnel with him, or even adequate medical attention in the subsequent two months, the assassination attempt would have been unsuccessful. Garfield was a capable and promising man, a young and much-promoted combat Civil War general and the only person ever to make the jump directly from the House of Representatives to the presidency (though he was also a senator-elect), but his loss was not as grievous as that of Lincoln.

President William McKinley was assassinated in Buffalo, New York, by an anarchist, Leon Czolgosz, in 1901, who had a handgun wrapped in a handkerchief when he shook hands with the president in a receiving line. Again, adequate security by contemporary standards would have prevented this, and again, competent medical attention would have prevented a fatality. The president was shot twice and the attending surgeon could not find the second bullet. Days passed with optimistic reports of the president’s recovery, but any informed person would have known that if the second bullet was not retrieved, acute septicemia was likely, and this was the cause of McKinley’s death.

It was a time of frequent anarchistic assassinations abroad, and Czolgosz had been inspired to commit this act by listening to a speech of the anarchist firebrand Emma Goldman (who often lived in Toronto, and died there). The United States did not have such discontented classes and ethnicities as there were in Europe, but there was no excuse for McKinley’s inadequate security detail and inept medical attention. This was again a terrible personal tragedy to befall a capable and well-respected president and a brave man who had risen from private to major in the Civil War entirely because of his courage and leadership qualities. Fortunately, he was succeeded by one of the nation’s most capable and popular presidents, Theodore Roosevelt.

All readers will remember or have seen film of the horrifying assassination of John F. Kennedy in Dallas on Nov. 22, 1963. The president of the United States has not travelled in an open car since then, and President Kennedy’s predecessors, Harry S. Truman and General Dwight D. Eisenhower, were just as visible in their official vehicles which had a bulletproof plexiglass roof. There has never been any explanation for why such a vehicle was not used in Dallas on that terrible day, though Kennedy’s penchant for convertibles was a factor.

In the last 100 years, five other U.S. presidents apart from Kennedy have been the subject of attempted assassinations. Then President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt, in 1933 in Miami, was the target of anarchist Giuseppe Zangara, who missed Roosevelt but shot five others, including the mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak, who died. Security was not as extensive as it has subsequently become, but it was only good luck that FDR was completely unscathed. He returned to Vincent Astor’s famous yacht, the Nourmahal, on which he had been cruising, had two stiff glasses of whisky (although prohibition, which he had always personally ignored anyway, had not yet been abolished), and never mentioned the incident again. Of course, he went on to be America’s longest-serving president, and one of its greatest.

The attempted assassination of President Truman in 1950 was fortunately incompetently conducted and the assailants did not get close to the president. But attempts on the lives of President Gerald Ford in 1975, Ronald Reagan in 1981, and Donald Trump this month, were only unsuccessful for miraculous reasons. President Ford’s first assailant, Squeaky Fromme, was intercepted as she fired, and the next, Sara Jane Moore, was jostled by a retired Marine. President Reagan’s security unit moved with commendable haste and courage and his bullet wound was only approximately an inch from being fatal. There was obviously a severe breakdown in appropriate security measures and coordination that almost cost the life of former President Trump in Pennsylvania on July 13.

As guns were involved in all of these assassination attempts and the Constitution, in fidelity to the revolutionary origins of the United States, guarantees the right of every law-abiding adult citizen to have a firearm, no screening process or restriction of firearms sales is going to reduce significantly the danger to presidents. All that can be done is to intensify security, and particularly to put bulletproof but completely transparent acrylic screens around presidents during public speeches. Crowds can now be scanned by metal detectors, and presidents travel in automobiles that are both bulletproof and bombproof. We have no idea how many attempts on the lives of presidents have been conceived but undone before they could be carried out, but the fact that six of the last 15 presidents have been threatened by assassins, and one of them murdered, shows that the danger is constant.

As long as there are discontented people who are severely deranged, the idea of killing leaders will have a simplistic appeal to them, as well as to a tiny echelon of terribly maladjusted people who imagine this to be a satisfactory route to historical fame. Assassins have not become more resourceful or ingenious since the time of Lincoln; it is for those entrusted with the security of the U.S. president to reduce the possibility of the success of assassins to the minimum. The same rules can apply to other elected figures who were victims of inadequate security, such as Robert Kennedy, assassinated in the kitchen of a Los Angeles hotel in 1968, and prominent non-presidential figures, such as Martin Luther King, also murdered in 1968, Malcolm X (1965), and Louisiana Governor Huey P. Long (1935).

Nor should we imagine that this problem is exclusively American. Margaret Thatcher was nearly assassinated by the Irish Republican Army on a couple of occasions, and Charles de Gaulle was almost killed by opponents of his Algeria policy several times. German interior minister Wolfgang Schauble was confined to a wheelchair for the rest of his life by an unsuccessful assassination attempt.

The problem may be slightly exacerbated in the United States because of the constitutionally guaranteed right to bear arms, but it is a universal problem, especially in democratic countries where leaders have to be relatively publicly visible. There is no antidote except better security and more and better-trained security personnel.

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times.