Japan has crucial military ambitions that could easily be derailed by leader indecision, complex politics and severe financial constraints

A US Marine Corps F-35B Lightning IIs flies near Mount Fuji, Japan, March 23, 2022. Picture: USMC

(Written by Jonathan Grady. Published here in Asia Times, originally published on Noah Smith’s Noahpinion Substack republished with permission.)

I’ve been writing a lot about the threat of a major war in Asia, but I haven’t written much about Japan’s role in that equation. And yet Japan would be at the very center of such a war. A Chinese seizure of Taiwan would put Japan’s security in grave danger. Here’s a translated quote from a Chinese PLA officer training manual:

As soon as Taiwan is reunified with Mainland China, Japan’s maritime lines of communication will fall completely within the striking ranges of China’s fighters and bombers…Japan’s economic activity and war-making potential will be basically destroyed…blockades can cause sea shipments to decrease and can even create a famine within the Japanese islands.

And China’s ambassador to Japan recently said that “once the country of Japan is tied to the tanks plotting to split China, the Japanese people will be brought into the fire.”

Given the extreme imminent danger, Japan’s defense policy going forward seems extremely important. I suggested that the country should deploy nuclear weapons, but there are probably plenty of other things the country’s leaders can do with regards to their conventional military capabilities.

One person with plenty of ideas is Jonathan Grady, a founding principal at the consultancy Canary Group, who has done strategic analyses of the Quad’s role in Asian security and who sometimes writes about Japanese defense policy. In this guest post, he explains some of the economic and political hurdles Japan will have to overcome in order to continue its defense buildup and ensure its own security.

Japan Must Soon Decide on Major Defense Buildup

Japan stands at a pivotal moment, facing urgent decisions about its defense strategy. Positioned to significantly enhance its defense capabilities, Japan is increasing its defense budget by 60% to assert more influence in Indo-Pacific security. This surge in spending is designed to bolster Tokyo’s deterrence against China and promote regional peace. However, the ambitious plans are jeopardized by leader indecision, a complex political landscape and severe financial constraints that threaten to derail the historic buildup. With the stakes high – shaping deterrence planning across capitals while colliding against political survival – the decision outcome is significant. As Japan faces an election year, the lack of political resolve and clear funding mechanisms compels sincere action to determine the future scope and financing of its defense ambitions. These choices will define whether Japan realizes its full defense potential or faces significant compromises.

Strengthening Japan’s defense posture

The historic post-World War II buildup aims to enhance Tokyo’s deterrence against Chinese aggression in the Indo-Pacific, a region crucial for global security. Additionally, it forms part of a broader international strategy to maintain a peaceful status quo amid competing territorial claims from China. Japan’s unique island geography and the vulnerability of American bases on its soil underscore the urgency of these plans. Notably, Japan has the world’s second largest fleet of advanced F-35 fighter aircraft and is buying hundreds of Tomahawk cruise missiles, enabling Tokyo counterstrike capabilities against enemy bases, and bolstering its defense and the security of American bases and troops.

Source: USAF

However, doubts over Japan’s political resolve and financial capacity to support increased spending create a high-stakes dilemma. Tokyo may not achieve some of the defense capabilities it previously planned. Even if Japan were to secure most of its wish-list items, potentially limited ammunition reserves from a constrained budget will hamper some of Tokyo’s newfound defense capabilities. Due to their close proximity to potential conflict, American bases in Japan are targets. Japan lacking previously planned capabilities is a disservice to these bases and soldiers. The Japanese government must soon address its defense expenditure dilemma because of due time pressures on defense budget funding and its security implications.

Image 3: Arleigh Burke-class guided-missile destroyer USS Barry launches Tomahawk cruise missile; Source: US Navy

Funding challenges and political indecision

While Japan’s defense ambitions are clear, the path to achieving them is fraught with financial and political challenges. Japan’s indecision over funding its surging defense budget undermines its buildup efforts. The lack of clarity over funding has left the buildup vulnerable amidst a challenging political landscape. With several delays in funding plans, the Japanese government faces an increasingly unfavorable political situation as time runs out.

As part of Japan’s new National Security Strategy, the Japanese government last year set aside a 43 trillion yen (approximately $300 Billion at the time) defense budget for five years, a 60% increase from previous defense spending. The expanded defense budget aims to help enhance deterrence against China and North Korea and equip Tokyo with counterstrike capabilities.

While the defense policy is popular among the Japanese public, the means to pay for it is not. This has led to chronic indecision on how to fully fund the spending increases over the past two years. The budget included one trillion yen (approximately $7.3 billion at the time) in tax hikes intended to help fund the increases, to be implemented at “an appropriate time in or after 2024.” This indecisive language was a compromise to delay unpopular tax hikes while expanding the defense budget. Unfortunately, the Japanese government delayed the hikes several times, now punting tax hikes to 2026. The ruling Liberal Democratic Party government asserts it will respect the planned defense increases, if the tax hikes are implemented by 2026. This further ambiguity raises concerns whether defense priorities will be fully funded or continue to be funded, and undermines the Japanese government’s credibility.

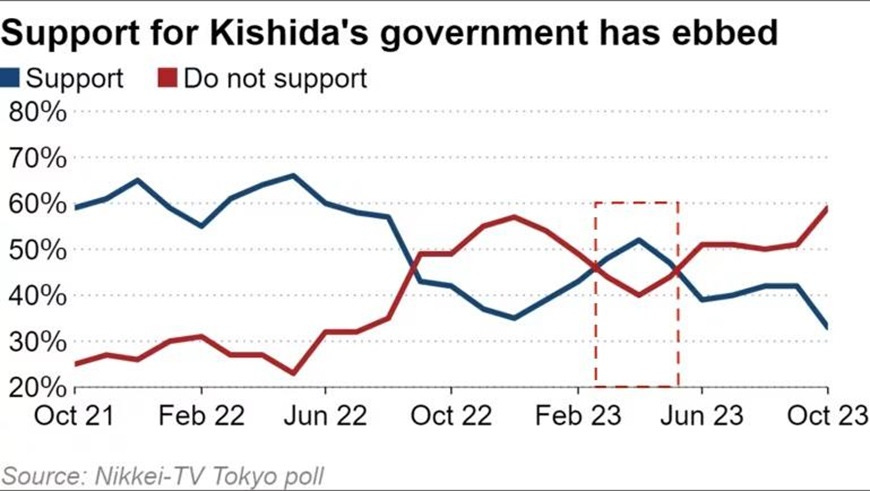

Compounding its indecision, the government flirted with calling an election for nearly a year. During the past summer, speculation peaked that the government would call an election to lock in electoral gains, as it was enjoying a spike in polls surpassing 50% in approval following foreign policy victories.

Unfortunately, the government did not call an election after months of consideration. The Kishida government approval polls then precipitously dropped, even before an unprecedented corruption scandal was publicly known. The Japanese government missed its best opportunity to call an election when it was at a point of strength, subsequently missing a major opportunity to secure its coveted defense funding. As highlighted by the Nikkei Asia graph, the Kishida government missed its optimal opportunity before the corruption scandal.

Source: Nikkei Asia

The indecision does not come as a surprise. In an analysis earlier this past year in Nikkei Asia, I indicated that the Japanese government needed to move fast on passing its tax hikes. If it did not pass the tax hikes quickly enough, it risked pulling back again on its tax hike timeline. I further indicated if enough time was allowed to pass, a coalition that included some of the inner circle members from the current government would resist the unpopular tax hikes. I indicated these individuals would adopt a politically motivated indifference. Since that time, Prime Minister Kishida announced abrupt cabinet changes, unsuccessfully shifting public opinion. Some of these inner circle members were seen as insufficiently loyal to the Prime Minister.

Significant political constraints compound the Japanese government’s indecision. The Japanese government severely wounded itself with a recent unprecedented political scandal; former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s faction, the largest faction in the Japanese government, was running a secret slush fund. The scheme implicated senior lawmakers, leading to resignations from the Prime Minister’s cabinet. The unprecedented scandal has created an unsettling backdrop and dealt a major blow for the Prime Minister’s agenda, with the unpopular tax hikes postponed and a nosedive in polls while he scrambles for political survival.

Government polling is now historically bad. A recent poll found approval for the Prime Minister’s cabinet dropped to 16.6%, the worst polling in over 10 years since the Prime Minister’s Liberal Democratic Party came to power in 2012. Another poll found a disapproval rate of 74% for the Prime Minister’s cabinet, among the worst polling in over 75 years since recording began in 1947. A Nikkei poll found a record high 69% disapproval of the Prime Minister’s cabinet since he came to office.

Unsurprisingly, unpopular tax hikes – even if meant for critical national defense spending – have been pushed aside at a time of historically unpopular polling. However, indecision over funding the spending increases persisted long before the drop in polls, detrimentally affecting Japan’s defense plans. Indecision also cost its leaders a significant opportunity to lock in its gains. Japan will need to find a way to pay for the defense spending increases. To address these funding challenges, the government has explored strategies related to asset sales, including a sale of government shares in NTT, a major Japanese telco. If Japan cannot fund its own defense buildup, the government’s prolonged indecision will damage planned defense capabilities and potentially its own credibility.

Economic hurdles in defense spending

Financial constraints further complicate Japan’s defense ambitions. Significant debt levels and the recent currency devaluation directly impact its ability to procure advanced defense systems, potentially compromising strategic initiatives. Raising debt to finance spending, a common practice in the past, now raises concerns due to Japan’s already substantial debt. There are concerns that Japan’s significant debt levels are now too high and could undermine the Japanese economy. Japan already carries substantial debt, prompting warnings from some economists.

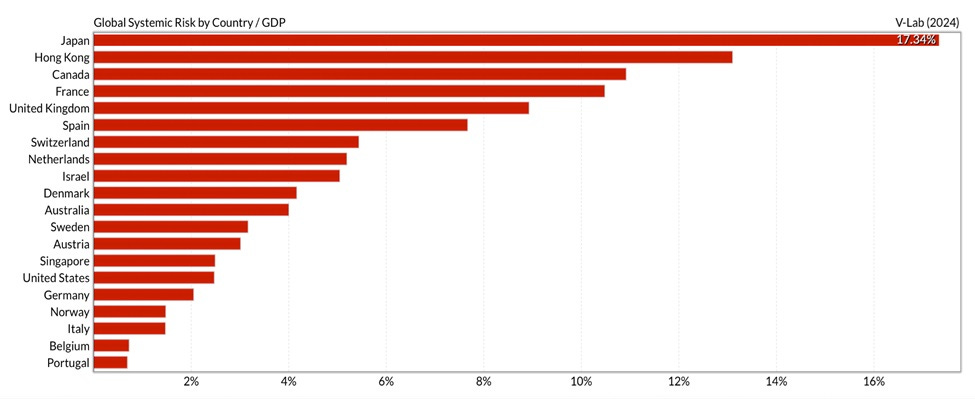

A prominent Japanese economist, responding to proposals for debt to fund the defense buildup, described a debt proposal as “unsustainable.” According to the NYU Stern Volatility Lab, when normalized for GDP Japan has faraway the largest amount of financial systemic risk from its debt among developed financial markets. In the event of a financial crisis, Japan’s systemic risk amounts to over 17% of its GDP. As illustrated below, Japan leads systemic risk among developed financial markets, highlighting economic vulnerabilities

Source: NYU Stern V-Lab

In the event of a financial crisis, Japanese banks risk a capital shortfall that would be highly damaging. If the Japanese yield curve were to surge, then the financial sector – mostly its banks – that own a large chunk of the Japanese sovereign debt will have collateral damage due to value losses. Japan is also a graying nation with over half its budget dedicated to social spending and debt servicing. Additional debt raises can further weigh against the government’s budget and create a more challenging financial situation for the Japanese government.

Compounding financial challenges, the recent drop in Japanese currency has reduced Japan’s buying power for defense acquisitions. The then-$300 Billion five year budget set in December 2022 questionably assumed a 108 yen to dollar exchange rate. However, the rate at the time was approximately 130 yen to the dollar; at the time, the lower 108 rate had not been seen in over a year since 2021. The exchange rate subsequently surged to over 150 yen to the dollar, further diminishing Japan’s buying power for major defense acquisitions.

Japan has already cut back some of its purchases of military aircraft, but it is yet to be seen whether further cuts will occur. The depreciating currency also reduces the buying power of the unpopular tax hikes meant to pay for defense. To continue with planned purchases, Japan will need more money to compensate for its depreciated currency and reduced buying power. Japan’s increasingly difficult financial situation only makes the politics over financing its defense buildup a more sensitive and challenging matter.

Japan’s role in Indo-Pacific security

Despite these hurdles, Japan has managed to play a pivotal role and see notable successes in regional security. Japan’s role is part of a broader and sophisticated effort to coordinate military efforts with allies and partners in the region to enhance deterrence against Chinese aggression and promote a peaceful Indo-Pacific region. This overlapping effort is one of the least understood, most complex and consequential trends in defense diplomacy.

Among its substantial efforts, Japan helps facilitate overlapping defense cooperation. Within the last year, Tokyo has signed significant reciprocal access agreements with the United Kingdom and Australia. Together with an existing agreement with the US, these agreements allow each country’s armed forces to train and operate on Japanese soil. A reciprocal agreement is also being negotiated with France, further expanding Japan’s coordinator role for foreign militaries. Another agreement under negotiation with US ally, the Philippines, would allow Japanese troops to operate on Philippine territory in the strategically critical South China Sea.

These agreements enhance interoperability and signal a unified stance against aggression, significantly bolstering regional deterrence and stability. The coordination meshwork means different partner militaries can train and operate on Japanese soil at the same time, enabling a higher degree of coordination with a larger number of armed forces close to China’s waters. While signaling deterrence, peacefully managing the relationship with China for Japan is still highly important. Prime Minister Kishida’s last meeting with Xi Jinping reaffirmed the two nations’ “strategic relationship.” Overlapping defense diplomacy is helping to enhance deterrence and promote a peaceful regional status quo.

This meshwork extends beyond Japanese soil with maritime cooperation. In a past project I originated for CNBC, I anticipated the extent of maritime coordination between Japan and other countries, while managing a continuing relationship with China. The larger implication is significant and poorly understood by experts because interaction with China is dynamic. The closer defense coordination helps promote regional peace from a shared mission, integrated defense efforts and increased costs associated with potential conflict. Japan’s defense buildup helps with these aims by supplementing coalition defense might. Whether Japan will be able to fully capitalize on its international leadership will require overcoming the challenges with its buildup.

Japan’s critical decision point

As Japan stands at a crucial juncture in its defense strategy, the decisions made now will shape its future capabilities and influence in the Indo-Pacific. These decisions will not only affect Japan’s security but also have significant implications for its role in regional security. With time running out and financial uncertainties looming, the stakes are high. The Japanese government faces a tumultuous political environment at home, severe financial constraints and a lack of decisive leadership. As an election year approaches, leaders balancing domestic and international politics must navigate these challenges decisively.

Action is required for Tokyo to secure the necessary financing, driven by national and regional security. In this high-stakes defense dilemma, it is crucial to recognize that leaders typically act in their self-interest. This self-interest has already led to a lack of decisive leadership regarding defense funding amidst an unprecedented government corruption scandal. To address Japan’s defense challenges effectively, leaders’ motivations must align with national defense. Whether this alignment happens will be a guiding north star during a pivotal election year, determining whether Japan can achieve its defense ambitions or face significant compromises.